Cyber-racism on online platforms

Global hyperconnection has merely evolved modes of racism from the local to the globalised. Social media platforms have come to be manifestations of community and society, reflecting thus the very same structures and practices of discrimination digitally, assisted, enabled, if not exacerbated by features unique to the internet: anonymity and pseudonymity, lack of accountability and direct repercussions, and the distancing of perpetrator and victim.

Background

Defining cyber-racism

Cyber-racism goes beyond interpersonal racism, encompassing all forms of racism made digital, from institutional to structural to systemic. A detailed outline of each of these forms of racism necessitates a much more in-depth analysis.

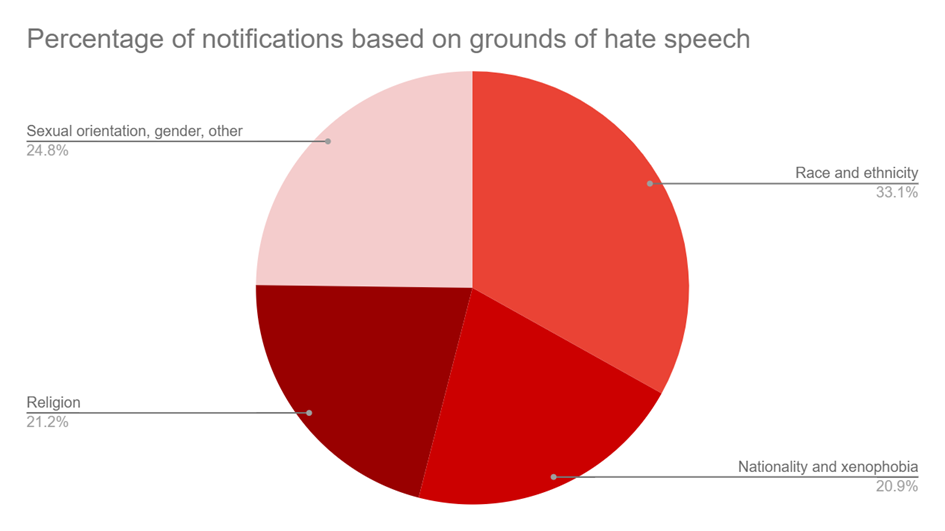

For the purposes of this study, interpersonal cyber-racism refers to discrimination based on race occurring between persons, perpetrated either individually or via groups, e.g. online hate speech. Some analyses involve other grounds of discrimination under the umbrella of racism, including religion, nationality, and xenophobia or anti-migrant hatred. This study particularly looks at race or ethnicity, but briefly mentions the other grounds in light of the EU Online Code of Conduct. Institutional racism refers to the policies and practices within or across sociopolitical institutions that generate racial inequality. Such institutions do not exist in a similar manner digitally, and institutional cyber-racism thus (often) manifests itself through the private actors developing and moderating much of the Internet today.

With regards to social media platforms, we will focus on interpersonal racism, focusing in particular on the experiences of racism of racialised persons online. We will also focus to some degree on institutional racism when analysing the policies and practices of social media platforms in platform moderation, as well as policy responses of the EU and the impact thereof.

Methodology

This analysis draws from, reviews, and visualises data collected from several conducted surveys, studies, and monitoring reports. The analysis will look at current data on the experiences of racialised persons online and assess this in light of the monitoring evaluations by the European Commission of the Online Code of Conduct. The analysis will look more specifically at current issues in platform moderation before closing on proposals for moderation reform.

Experiences of racialised persons online

Various studies point to a marked increase in instances of discrimination online, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic. However, specific data on the experiences of persons based on racialised or ethnic identity is not surveyed in Europe as it is in the US – survey data on the latter will thus be used for this analysis.

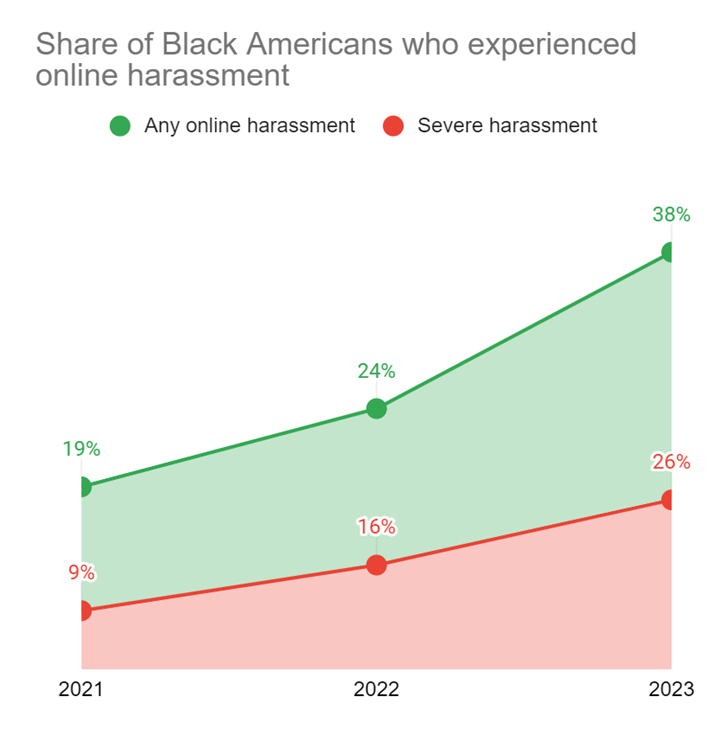

In the US, a YouGov Survey found a significant year-on-year increase in harassment, including severe harassment, reported by Black Americans from 28% in 2021, to 40% in 2022, and 64% in 2023.

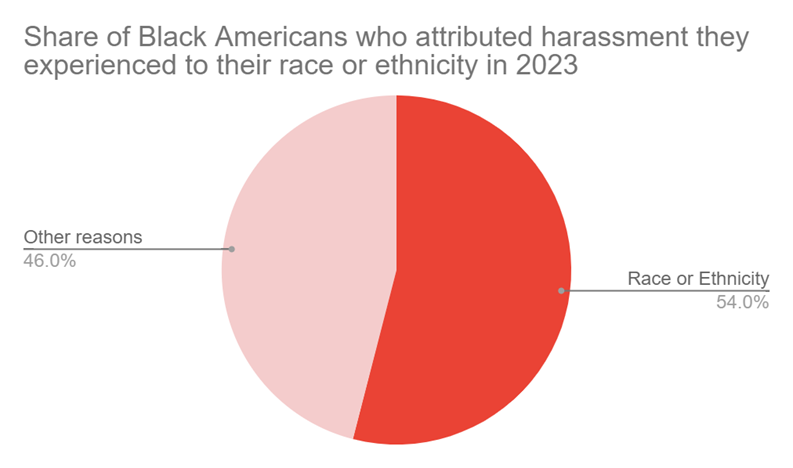

Of this 64% of Black Americans who experienced online harassment, slightly more than half (54%) attributed said harassment to their race or ethnicity. As such, around 1 in 3 Black Americans have faced online harassment because of their race.

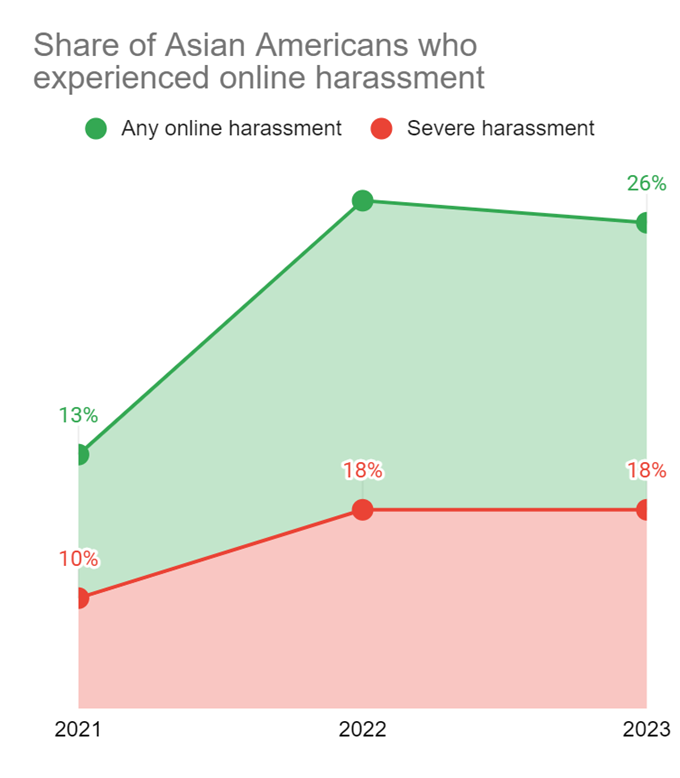

Though the share of Asian Americans who experienced online harassment fell in 2023 to 44%, there was a significant increase in harassment from 23% in 2021, to 46% in 2022.

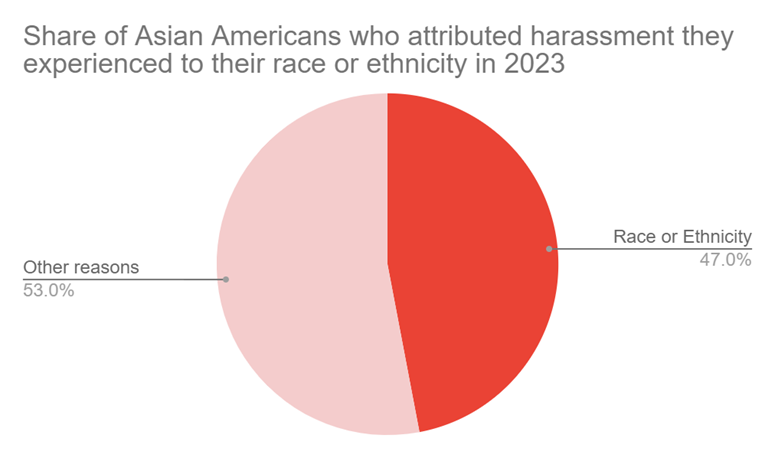

Of this 46% of Asian Americans who experienced online harassment, nearly half (47%) attributed said harassment to their race of ethnicity. Thus, nearly 1 in 4 Asian Americans have faced online harassment because of their race.

Ineffective moderation?

Despite the concerning rise of online harassment of racialised persons, regulatory efforts, both by regulatory authorities and the industry itself, have shown no significant impact.

In response to the rise of online discrimination, and as part of the EU’s anti-racism action plan, the European Commission adopted the Code of Conduct on Countering Illegal Hate Speech Online, a voluntary set of policies agreed with Facebook, Microsoft, Twitter and Youtube in May 2016, the implementation of which is evaluated through a yearly monitoring exercise and through a commonly agreed methodology allowing for comparison over time. Instagram, Snapchat and Dailymotion took part to the Code of Conduct in 2018; Jeuxvideo.co in 2019, TikTok in 2020, LinkedIn in 2021, and Rakuten Viber and Twitch in 2022.

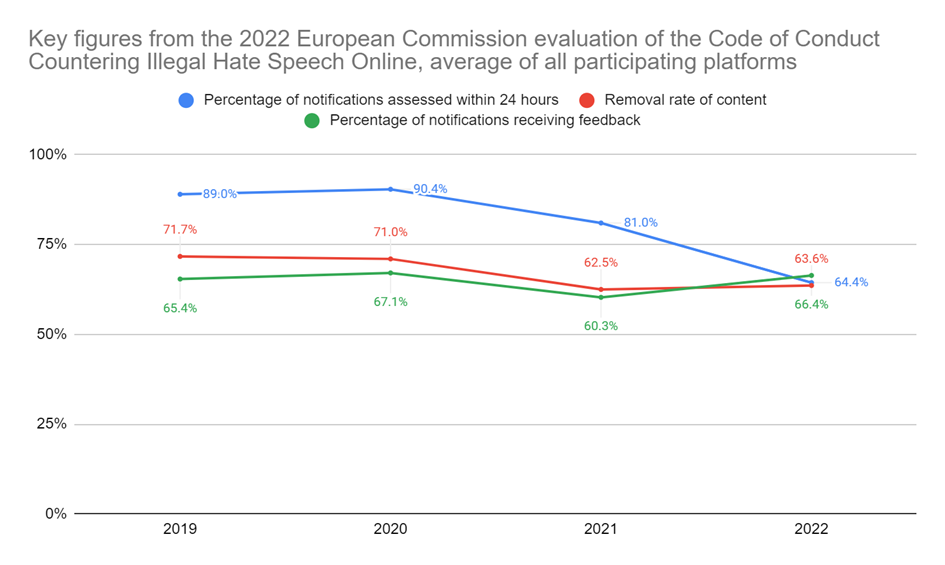

Key figures from the 4th to 7th evaluation of the Code of Conduct shows little progress between 2019 and 2022. Notably, the assessment times of notifications based on the Code of Conduct’s target of assessment within 24 hours has been steadily decreasing relative to 2019, a fall from 89% on average in 2019 to 64,4% in 2022. Only TikTok had a better performance than in 2021, while all other platforms measured worse.

Two other key indicators of the Code of Conduct have shown minor improvement between 2021 and 2022, however with no significant improvement year-on-year and a decrease from their peaks in past years.

The removal rate of content notified has fallen from 71,7% on average in 2019 to 63,6% in 2022. Only YouTube had a better score than in 2021, while all other platforms measured worse.

Meanwhile, the percentage of notifications receiving feedback remains insufficient, with marginal improvement from 65,4% on average in 2019 to 66,4% in 2022. YouTube in particular scores significantly lower than other platforms, providing users feedback in 13,5% of notifications, a score more than 50% lower than the average.

It is also worth noting that the most commonly reported grounds of hate speech are some form of hatred based on race, ethnicity, religion, or nationality – measuring at 75,2% of all notifications.

As it stands, the Code of Conduct, amongst other measures taken by major online platforms, shows little actual year-on-year change, if not a fall in aspects such as assessment times, while incidences of cyber-racism continue to rise year-on-year. It is also worth challenging the indicators in which ‘success’ tackling online hate is measured, as content removal for example, as will be highlighted below, does not necessarily entail better protection of marginalised communities.

Double standards and discrimination in platform moderation

Another shift since the COVID-19 pandemic has been the decrease of human reviewers, and increasing use of automated tools in the moderation of online platforms, and it is not clear if platforms have subjected these tools to any form of independent review for accuracy or efficacy.

Current biases within automated processes for reviewing and removing content contradictorily puts speech from marginalised communities at risk of over-removal. The automated flagging and removal of terrorist content, for example, has led to the restriction of Arabic-speaking users and journalists. Studies have further found that automated tools incorporating natural language processing to identify hate speech instead amplify racial biases. Models for automatic hate speech detection were 1.5 times more likely to flag tweets of Black people as offensive or hateful, with tweets in African American Vernacular English (AAVE) twice as likely to be labelled as ‘offensive’ or ‘abusive.’ Another study on five widely used data sets for studying hate speech found ‘consistent, systemic and substantial racial biases in classifiers trained on all five datasets.’ This could be attributed to an inability of such tools to understand contextual nuances in the use of language, such as terms which amount to slurs when directed against marginalised groups that are used neutrally or positively within that group; to the inadequacy of training data in other dialects or languages; to the translation of norms and notions of hate speech from one cultural and lingual context to another.

Human moderators can similarly amplify racial biases simply due to increasing workloads and pressure to finish their queues. This is further exacerbated by the externalisation of moderation to remote countries relative to the market moderated, and as such a lack of local and cultural knowledge or even appropriate language skills to accurately make determinations on content. Furthermore, the increase of regulatory corporate accountability for such hatred without sufficient safeguards or limits or even the threat of government regulation has led to a tendency towards risk-averseness and to remove content than not.

Platform rules governing terrorist content, hate speech, and harassment themselves are designed to give platforms broad discretion, with broad and imprecise application against marginalised communities, yet narrow against dominant groups. Coupled with overbroad tools for mass removals has resulted in ‘mistakes at scale that are decimating human rights content.’ Power dynamics are also not fully incorporated in rule construction, as seen in an internal Facebook training document from 2017 revealing that, in a set of female drivers, Black children, and White men, under its hate speech policy, only White men would be protected due to its distinction of protected and quasi- or nonprotected characteristics. This has resulted in inequitable enforcement practices that seemingly protect powerful groups and their leaders whilst subjecting marginalised groups to over-enforcement or -removal.

As such, current platform policies and practices, including an increasing shift away from human reviewers towards (purely) automated moderation, subject marginalised communities to heightened scrutiny and risk of over-enforcement, whilst insufficiently protecting them from harm.

A need for platform transparency and regulation

A crucial starting point towards more equitable and effective moderation of cyber-racism begins at more transparent practices. The Commission has stressed feedback and transparency to users as one of its key indicators in tackling online hate. With the DSA coming into force at the end of 2022 and subsequent obligations on transparency and feedback to users’ notifications, it remains to be seen how this impacts consequent monitoring assessments of online hate.

Moreover, platforms need to reform moderation to ensure that the voices of racialised communities are centred, and thus reorient moderation towards not just their protection but towards repairing, educating and sustaining communities. This requires the involvement of racialised communities in the formulation of moderation rules and policies, and a reassessment of the connection between speech, power, and marginalisation in the drafting of such policy, in the training of automated tools, and in the enforcement of moderation. As AI development continues, and thus its involvement in platform moderation, the inherent racial biases within it need to be challenged.

Comprehensive and systematic reform to platform moderation is essential to combatting cyber-racism, and where this cannot be expected from platforms themselves, legislators must intervene to ensure platform accountability, transparency, and fairness, and the equitable protection of the marginalised made digital.

Amazing and extremely important work.

It sad that we can’t have such detailed data on Europe….

A very interesting read, but saddening to see that cyber-racism is so prevalent.